“The best plan is only a plan, that is, good intentions, unless it degenerates into work. The distinction that marks a plan capable of producing results is the commitment of key people to work on specific tasks. The test of a plan is whether management actually commits resources to action which will bring results in the future. Unless such commitment is made, there are only promises and hopes, but no plan.”1

Peter Drucker

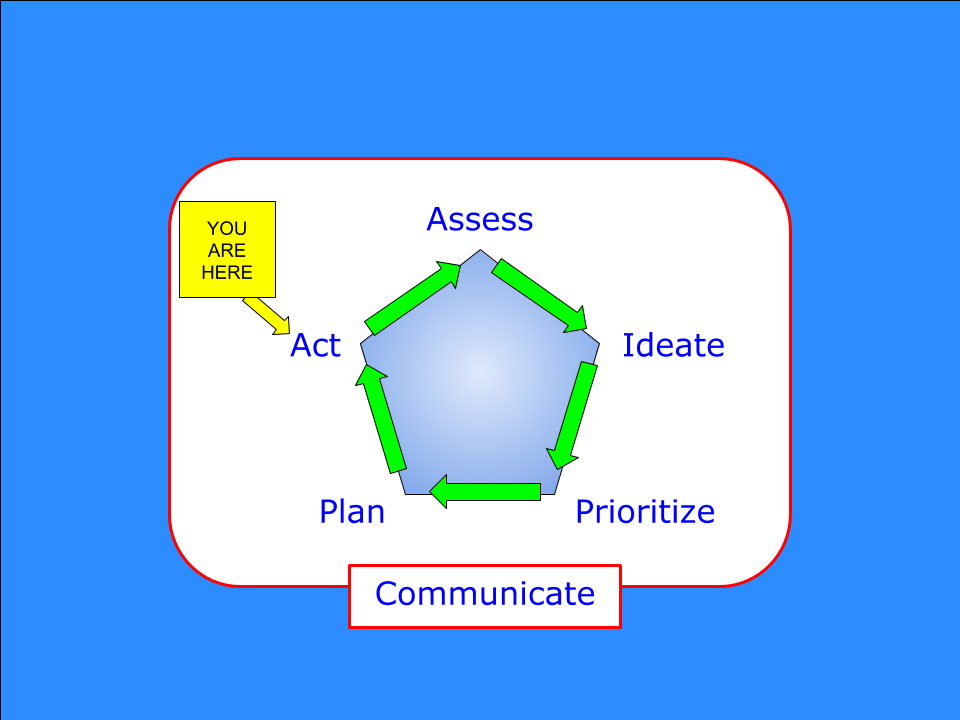

This is the last in a series of articles about planning in uncertain times. In the first article, I introduced the framework – a repeatable cycle made up of six phases. The other articles are:

- Phase 1 – Assess

- Phase 2 – Ideate

- Phase 3 – Prioritize

- Phase 4 – Plan (Part 1 – Developing a Plan)

- Phase 4 – Plan (Part 2 – Refining Your Plan)

- Phase 5 – Act – this article

- Phase 6 – Communicate

Introduction

So here we are. We’ve spent several months working through the phases of the planning cycle and now have a well thought out, actionable plan with clear objectives and measures of success. But according to Drucker, what we have accumulated is a just a bunch of good intentions, promises, and hopes. We are at a critical juncture, a place where many people stop, afraid to commit, unwilling, or unable to move ahead with actually implementing their plan.

But not you. You are a manager who gets results. All the work you’ve done up to now is preparation. You know that planning without execution is a wasted effort. Execution – taking action to implement your plan – is what separates the dreamers from the doers. This is where you deliver the results expected by your organization…and then some. (My definition of success.)

And it’s not like you’ve been sitting idle, waiting to blow the whistle and start the action. You’ve got your day job to do. You’ve probably already been working on some aspect of your plan, trying to get a head start.

So how do you shift from planning to acting? For some managers on some projects, there will be a lot of fanfare. Kickoff meetings. Speeches by the executive sponsors. PowerPoint presentations. Cake and punch. Everybody will get fired up and then charge out to slay the dragons.

At the other end of the spectrum, the day you launch your project is just like any other day. Sure, your to-do list includes some new items. But your team is already working, heads down, grinding it out.

The activities in the Act phase are a combination of tactics and style. Your role now expands from manager to leader.2 You will be coach, scorekeeper, cheerleader, counselor and sometimes the pizza delivery person. The Act phase will require all your talents and will test all of your skills. It’s why many of us became managers in the first place.

Let’s get into the details.

Your Role in the Act Phase

There are seven activities that you will perform during the Act phase:

- Lead from the front

- Get out of the way

- Monitor status and progress

- Eliminate obstacles

- Adjust the plan as needed

- Communicate, communicate, COMMUNICATE!

- Celebrate success

We’ll look at each of these in turn.

Lead from the front

You are the leader of this initiative. Your responsibility is to set the tone and pace of the effort. To do that, you’ll need to be out in front of your team. You’re going to encourage them at the kickoff meetings and every day afterward. You’ll also constantly remind them of the objectives they are setting out to accomplish.

You also have to be out in front of sponsors and stakeholders, reminding them of the objectives, eliciting their support and listening to their concerns. And as you make progress on implementing your plan, you’ll need to keep them informed about what has been accomplished and prepare them for what will be done next.

Get out of the way

This might seem to contradict the last point, but you must let your team do the work they signed up to do. You need to be a “macro-manager”, not a “micro-manager”. Trust your team to do their jobs. You have plenty of work to do, but not their work. Encourage your team, support your team. Bring them pizza. Just don’t try to do their work.

Monitor status and progress

This doesn’t mean you’re completely hands-off. Managing a major initiative means maintaining a close watch over the activities. You want to determine how the team is progressing towards the objectives and what obstacles they are encountering. You can do this by establishing a regular routine for collecting information and feedback from your team. This could include daily standup meetings with team leaders. You may also ask for written progress reports or status updates in an online database.

How often should you collect the reports? You may have to experiment with timing to determine what works best in your organization. Settle on a cadence that provides you the details you need while minimizing the effort your team must spend providing it.

You have a robust set of tools, developed in the earlier phases, that will help you evaluate progress and identify obstacles:

- The project plan. It describes who’s doing what, when, and for how long. By monitoring the status of tasks in the plan, you’ll be able to see when the project is going off schedule or where interdependent tasks are not timed correctly.

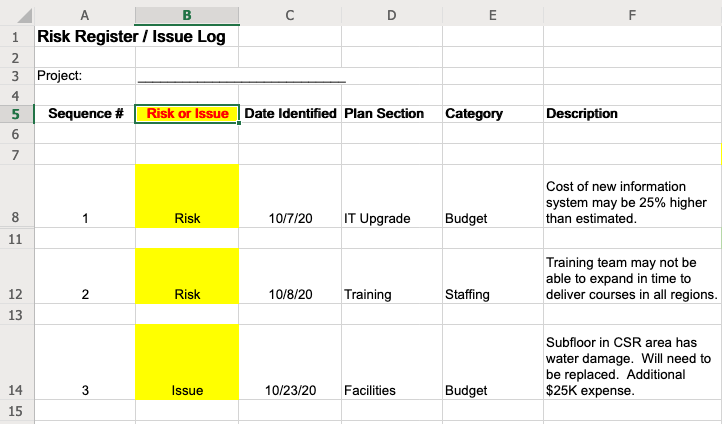

- The risk register. You have already identified some risks that could impact your plan. Continue to monitor the status of the risks to determine if the probability is increasing or decreasing.

- An issue log (new). Your risk register needs to expand to include an issue log. Risks are events that might occur in the future. When a risk event actually occurs, it becomes an issue. Many issues are unexpected. Whether anticipated or not, you need to prioritize the issues and determine how to address them.

The Risk Register template has been updated to include Issue tracking.

- Your list of assumptions. Continue to review the assumptions you identified during the Plan phase. If you see that an assumption needs to change, you’ll have to assess the potential impact on your plan, schedule and budget.

- The project budget. You must monitor your project’s actual spend against the budgeted amounts. Unexpected expenses will occur. Sometimes these can be offset by savings in other areas, but major unplanned expenses can be catastrophic for your initiative. Your boss and your steering committee will hold you accountable for your budget. Be sure you are aware of how the money is being spent. My guiding principle was to always treat the company’s money as carefully as I treated my own.

- Your progress and success measures. In the Plan phase you identified measures that indicate progress toward the objectives and measures that represent successful attainment of the objectives. Both should be monitored and reported on throughout the project. They will provide valuable feedback for your team and your stakeholders.

Eliminate obstacles

A critical role you play as the leader of the team is getting rid of the obstacles that impede the team’s progress. You’ll hear about some of these during your status meetings and in your day-to-day conversations with team members, but you also need to ask “what’s stopping you from making progress?”

Over the course of my career I heard hundreds of different answers to this question. Most of the time it was about something happening that was different from what was in the plan. Sometime it was something completely unexpected. Most answers fell into one of these categories:

- “We’re not sure what to do in a particular situation.”

- “We’re waiting on <something to happen> or <someone to act>.”

- “We’re facing resistance from a key stakeholder group.”

- “We have a conflict with another team or person.”

How you respond to each of these will also vary widely, depending on the people involved, the significance of the problem and the urgency to get it solved. Here are some general approaches that I found useful:

- Ask questions to ensure you understand the situation or obstacle.

- Ask questions to find out what actions have already been taken or what possible solutions have been tried. Why didn’t those resolve the problem?

- Ask questions about what possible solutions have been identified, but not yet tried. If they haven’t been tried, why not?

- Determine if the problem should be addressable by team members. You may need to coach or answer their questions, but don’t assume every problem raised is one you have to handle.

- If it’s your problem to resolve, let the team members know what you plan to do and when you’ll reply back to them. Keep your promise!

Some obstacles will be very visible. Others may be outside of your view. Your ability to understand and address these hidden obstacles depends on the level of trust you have established with your team. You want to encourage the free flow of timely information. You can’t help prevent a major issue if you don’t hear about it until it’s already on fire. Let your team know you want to hear the problems and the bad news first. Demonstrate your sincerity and trust by appreciating those reports, not by “shooting the messengers”.

Adjust the plan as needed

No project plan is ever complete until the project is over. You will make adjustments throughout the Act phase. Many will be small, with little impact to the overall timeline or budget. But there will be occasions where more drastic changes may appear necessary.

As I said in the second Plan article, “Refining Your Plan”, use caution when considering major changes to your plan. These can be disruptive to your team’s momentum and can raise doubts in the minds of sponsors and key stakeholders. So be sure that a change in the plan is really needed.

If a change is being suggested because of new learning, changes in assumptions, or unexpected issues, then it may be warranted. But if the change is being suggested because the team is encountering resistance to the plan, you should first take other actions that leave your plan intact.

You may need to directly intervene to address the source of resistance. Who is standing in your way? What are their grievances? You may need to request help from colleagues, sponsors, or leaders of other groups where the resistance is located.

An alternative to making radical changes to your plan is to rearrange the order of plan activities to eliminate the issues. I did this on one of the first global projects I ever managed, over twenty years ago.

In the mid-1990’s, I led a team that was implementing Lotus Notes as the new email system in our company. This was a dramatic change from the text-based messaging system that had been in use for many years. Our plan called for a phased implementation by region, with North America first. We had decided that we would install Notes in the corporate headquarters first, so that key executives and business leaders could experience the benefits early and become advocates for the program across their organizations.

But early on, we encountered stiff resistance from different groups. It quickly became apparent that doing the HQ first would be a long, hard slog that would create significant delays in our schedule. At the same time, we were hearing urgent requests from teams in Asia, who were anxious to get the new system.

This was around 1997 and the concept of “pivot” hadn’t been invented yet. But that’s what we did. We stopped work in the headquarters and shifted our focus to Asia, where our implementations were enthusiastically received. From there, we went to other regions where we heard demand. After about a year, we started hearing requests from the headquarters teams, usually like this, “Uh…we’ve been hearing about this new Lotus Notes thing. It sounds pretty good. When can we get it?”

I’d be lying to you if I didn’t admit to the sweetness of our reply: “We’ll see if we can work you into the schedule.”

But of course we did. There were still lots of issues to resolve, as in any major program, but by changing the order of planned work, we were able to accomplish our objectives without wrecking our schedule at the outset.

Be proactive. Your job is to hit the objectives and deliver the results. But don’t tear up your plan at the first sign of trouble.

Communicate, communicate, COMMUNICATE!

Communication was an integral part of each of the earlier phases. Keeping stakeholders informed was important then. It’s even more important in the Act phase. One difference is that, in the earlier phases, communication was something you did at the end of the phase – you were reporting on what had been done. But as you are implementing your plan, communication will be a constant activity. You’re going to be communicating before, during and after.

Your stakeholder analysis and communications plan will provide structure for your communications. Your stakeholder base has now grown to encompass many different groups. There is the team you assembled to do the initial assessment, your executive sponsors, other high power stakeholders, and any groups that are impacted by the plan you are implementing. These groups will have different information needs, so you will be creating multiple communications, including:

- Status reports to sponsors, steering committees and the groups who are collaborating with you to implement your plan.

- Progress reports to impacted stakeholders. These will initially alert them to the changes coming and over time will inform them of how the work is proceeding. These reports are good opportunities for you, and others, to talk about early successes and the cumulative benefits of the project.

- Leadership messages. Leaders and other managers throughout your organization may need to promote your plan with their teams. You can help by providing them with talking points, presentations, and other materials to ensure that they are on message. Give them an easy script to follow and you help ensure that a consistent message is delivered across the organization. If there are specific behaviors that leaders need to model in order to “walk the talk”, you should spell these out in detail.

Celebrate success

You and your team have worked hard to get to this point. Make certain that you find ways to celebrate the team’s accomplishments along the way. It’s not necessary to wait until the end of the project. Small celebrations at major milestones can provide a boost to team morale, particularly if the project has encountered problems along the way.

Find ways to make individual contributions visible to your sponsors and leadership team. Your role as manager is to highlight the achievements of your team – to let them shine. If there are problems or significant issues, your job is to take responsibility for them – not to blame your team. Remember, the buck stops with you.

Conclusion

We have now completed the planning cycle. You have gone from identifying a problem to successfully implementing your plan. You have delivered results…and then some. So, take a deep breath, celebrate a little, and enjoy a long weekend. Then get prepared to start the cycle again. Because that’s what we, as managers, do.

Making change in our organizations is never easy. But by taking a structured approach to planning and implementation, you can make the outcomes more predictable.

This series of articles has been challenging to write. I’m sure they have been challenging to read. I hope you have gotten some actionable ideas from them. If you found them valuable, please recommend them to a colleague. If you have questions or want to disagree on any of the points, please let me know by posting a comment below or sending me a note through the contact form.

To your success,

Footnotes

1 Peter Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York, Harper & Row, 1985), p. 128.

2 In a future article I will articulate the difference between “management” and “leadership”. They are not the same thing!

Help me set the agenda for future articles.

It’s time to move on to other topics.

I’d appreciate your suggestions on what subjects you’d like to hear about next.

Add your thoughts in the comments below, or send me a note through the Contact Form.

Thanks!