Why this topic today?

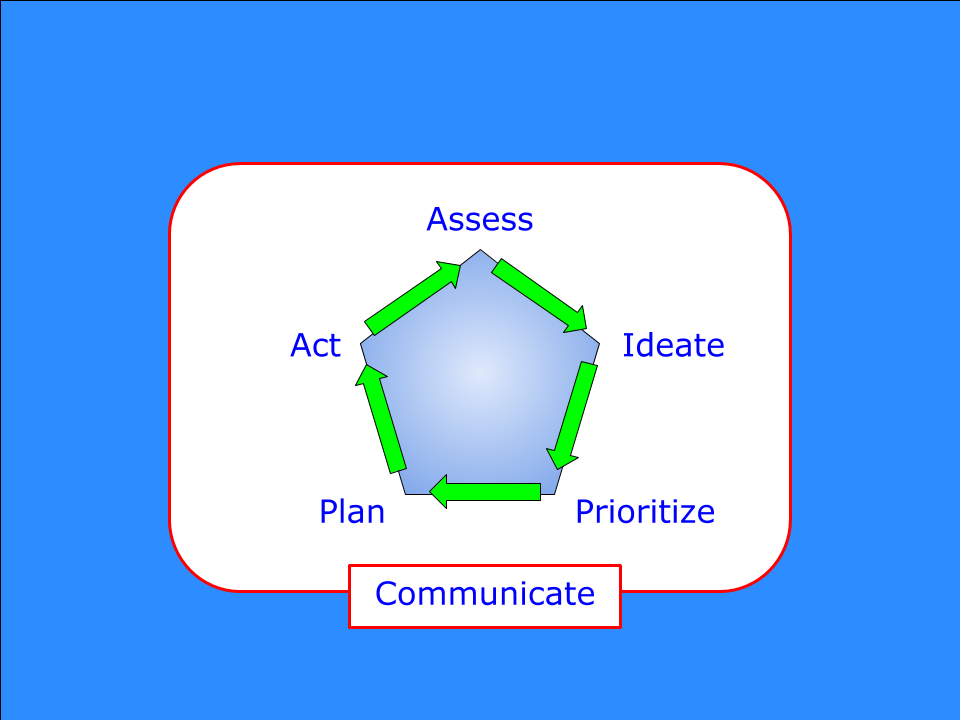

In today’s article I want to explore how we, as managers, can gain more insight into the concerns and interests of our stakeholders. For those of you who have following my most recent articles on the Planning Framework, this may seem like a detour. But this article is more of a prerequisite piece for the one I’ll publish next on the Communicate Activity.

My thesis is that in order to communicate effectively, you have to understand your audience. The Stakeholder Analysis method I’ll describe below provides that understanding, which will benefit your communication efforts and other areas of your management practice.

OK. Enough preamble. Let’s jump in.

Introduction: Who are Stakeholders and why should we care about them?

As managers, we know our jobs are to make things happen. My definition of success for a manager is that “you deliver the results expected by your organization…and then some”. This doesn’t happen in a vacuum, and we certainly don’t do it alone. We work in organizations filled with people. Our organizations exist in companies, industries and communities made up of people and other organizations.

Some of those people and organizations have an interest, a “stake”1, in the work we do. They are our “stakeholders”. Some of them depend on us and we depend on some of them. Some of them are supportive of our work. Others may be threatened by it. Many of them, supporters and detractors, will want to influence the direction of our work. Some of them will have the power to help us move forward or to stop our work completely. And many of our stakeholders will have little interest in our work at all, until it impacts them directly.

Knowing who your stakeholders are and understanding their interests has a direct relationship to your ability to deliver results. It has a direct impact on your success as a manager.

It’s useful to think of stakeholders as internal – those within your organization – and external – those outside of your organization. A short, and incomplete, list of stakeholder types would include the following people and groups.

For the purposes of this article, I’m going to focus on internal stakeholders, but many of the ideas will also be applicable to external stakeholders.

Stakeholder “Management” or Stakeholder “Engagement”?

Most discussions about how to deal with stakeholders focus on the idea of stakeholder management. This suggests that the purpose is to convince them to do what you want. UK author Mike Clayton recommends thinking about stakeholder engagement, “the process of entering into a respectful, constructive dialogue with our stakeholders”.2 Since some stakeholders can exert significant influence over your work, having a dialogue with them is a good idea.

There are multiple reasons you will want to engage with your stakeholders, including:

- To communicate about your work or projects.

- To elicit support for ongoing work or particular projects.

- To identify detractors, both potential and real – the people who could derail your work.

- To identify and manage risk.

- To identify stakeholder needs that could lead to new product and service offerings.

Stakeholder Analysis – The Starting Point for Engagement

With so many different types of stakeholders, it can be difficult to know who to start with and how to approach them. The process of stakeholder analysis helps you identify your stakeholders and prioritize your engagement activities. Analyzing your stakeholders is a prerequisite for your overall program of stakeholder engagement. (It is also a necessary component of a communication plan, as mentioned in the Communicate activity in the Planning Framework.)

There are four steps in the Stakeholder Analysis process:

- Identify your stakeholders.

- Collect information about your stakeholders.

- Analyze your stakeholders.

- Plan your interactions with your stakeholders.

We’ll consider each in detail.

Stakeholder Analysis should be an ongoing activity. You will iterate through these steps many times and sometimes will be doing multiple steps in parallel. Thus, you can start with the mindset that it doesn’t have to be perfect the first time through. You’ll improve your analysis with each iteration.

Identify your stakeholders

Unless you are brand new to your organization, you probably have a pretty good idea of who your stakeholders are. You can generate a list of stakeholders by answering a single question:

Who are the persons, groups or organizations who could influence my ability [or my team’s ability] to deliver results?

You may end up with a long list. That’s OK. But if you think you might have missed some stakeholders, enlist the help of your boss, colleagues or team members. Having key members of your staff engaged in this process will provide useful perspective.

It will be helpful to group the stakeholders on your list by type, such as direct staff, peers, senior executives, and others as shown in the table above. Add other types as needed.

This list will change over time, as you identify new stakeholders and as people change roles or leave the organization.

Collect information about your stakeholders

The next step is to collect some basic information about your stakeholders. Some items will be readily available, like:

- The stakeholder’s name.

- Type of stakeholder (colleagues, manager, senior executive, etc.).

- The stakeholder’s organization.

- The stakeholder’s role in their organization.

Other items may require direct conversation with the stakeholder, observing their activities and listening to their comments. You may also need to solicit input from colleagues, team members or your boss. These items include:

- The stakeholder’s level of interest in your work.

- The amount of power or influence the stakeholder has over your work.

- The stakeholder’s attitude about your work. Are they a supporter or a detractor?

Finally, make notes about anything else you know or learn about the stakeholder that will help you engage more effectively with them.

The graphic below illustrates a simple template for capturing this data.

Download the Stakeholder Analysis template.

All templates are free to download. No subscription required. Read more here.

During your first iteration of the process, collect what you know or can reasonably estimate. You’ll refine your data and collect missing pieces over time.

In an earlier article, I suggested an approach for conducting one-on-one meetings with employees, colleagues and others in your organization in order to build effective relationships. These meetings present an ideal opportunity to collect information and impressions about your stakeholders.

It is not necessary to have a face-to-face discussion with every stakeholder in every group. For some stakeholder groups, it might be appropriate to send surveys or to collect responses from help desks or call centers.

You can also gather useful information simply through observation. For example, if one of your Steering Committee members spends most of her time in your meetings looking at her phone, you might conclude that her level of interest is low. (You’ll want to verify that conclusion as noted below.)

The information you collect will be a mix of factual data and subjective opinion, both of which should be periodically reconfirmed. It’s probably a fact that your organization’s financial controller has power over your work through the budget approval process. But it your opinion that a business colleague is a detractor of one of your projects should be confirmed through further observation, listening and direct conversation.

Tell me more!

Subscribe to MyManagementMentor

Every two weeks you’ll get an email with a link to the latest article.

No spam. Ever.

Analyze your stakeholders

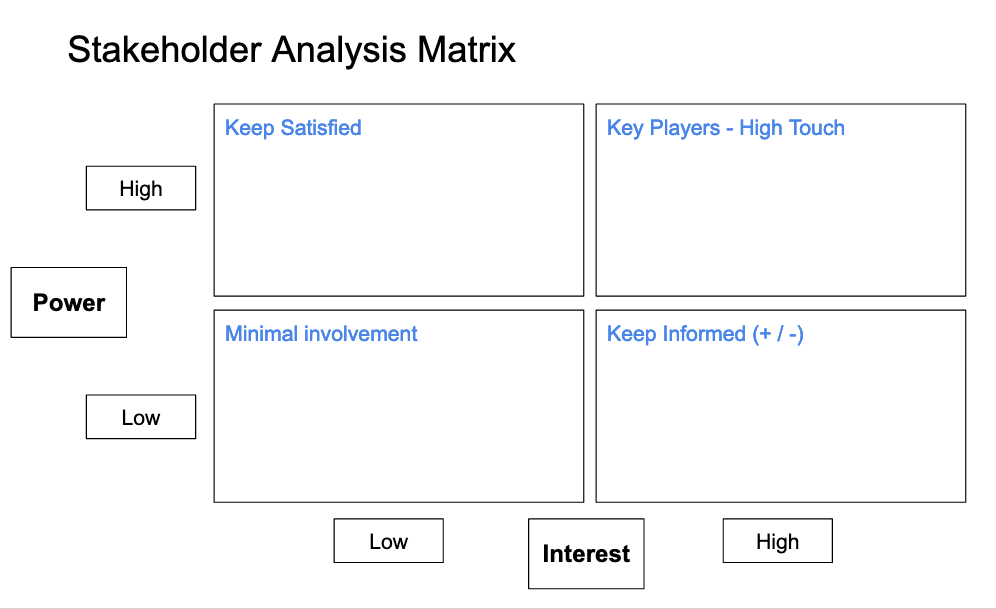

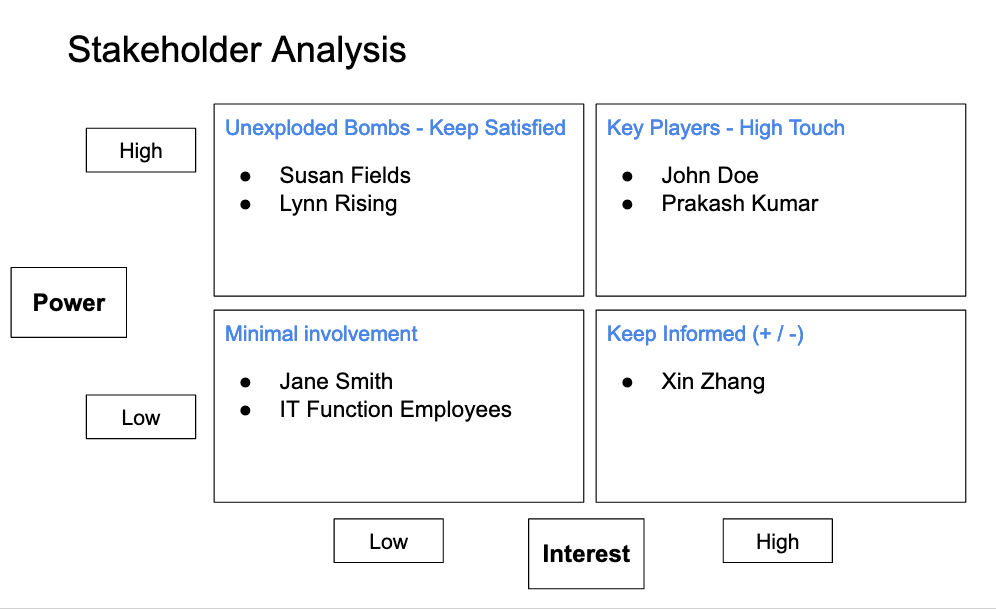

The next step is to analyze the information about your stakeholders. This can, and should, be done in parallel with the information gathering. For this step we will use a stakeholder matrix that allows you to plot stakeholders on a two by two matrix with “Power” and “Interest” as the two axes.

Download the Stakeholder Analysis Matrix.

All templates are free to download. No subscription required. Read more here.

As you collect information about your stakeholders, you can add their names in the appropriate area in the matrix.

Again, this is an ongoing activity, so over time you will review and revise your analysis. Changes in the organization will result in people being added or removed from your stakeholder list. You will be aware of, and possibly contribute to, changes in the level of interest or attitudes about your work.

Plan your interactions with your stakeholders

The analysis template and the matrix are useful tools for planning how and when you engage with your stakeholders. Each quadrant of the matrix requires a different approach.

- High Power / High Interest. These are your most important stakeholders, the ones with whom you will want to invest the most time and effort. In addition to seeking their opinions, you may also need to involve them directly in your work by inviting them into your decision making process or through membership in governance boards and steering committees.

- High Power / Low Interest. These are stakeholders who you want to keep satisfied. One way to think about them is that they are unexploded bombs – while they don’t appear to pose a threat, that could change at any minute. You want to keep them informed and understand their concerns.

- Low Power / High Interest. While they hold little power to directly impact your work, these people or groups can be important influencers across the organization, particularly if you are leading a transformational change effort. If they have a positive impression, you will want to keep them informed and maintain their enthusiasm. If they are detractors, you may need to engage with them to understand their concerns and attempt to change their perspective. In either case, they may place excessive demands on your time, which you’ll need to manage carefully.

- Low Power / Low Interest. There will be a temptation to ignore this group of stakeholders. While they will not require much attention, you should provide them with general information when appropriate. Also, you should monitor their attitudes to be aware of any changes. Persons in this group may also move into different roles, which could change their power and interest levels.

In my next article on the Communicate Activity, I will provide additional information about different tactics for communicating with stakeholders.

Two cautionary notes

First, it is important to recognize that the act of soliciting opinions or collecting information from your stakeholders can create expectations in their minds that you will act on their input or use their opinions to shape your decisions. Be aware of that, particularly with high power \ low interest stakeholders and communicate clearly.

Hoa Tran, of Darzin Software in Australia, comments that

“Consulting people entails a promise that at a minimum their views will be considered in the project’s decision making process. Showing that you are genuine in your engagement approach by following up on this promise is key to building long-lasting and trusting relationships. It does not mean that every issue must be acted upon, but the company must make best effort to address key issues through changes in the project design and decisions. Be upfront and honest about the limitations, challenges, and barriers in meeting stakeholder demands. It is part of managing stakeholder expectations and building trust.”

Second, I recommend that you treat your analysis work as internal information for your use and your team’s use in managing your work. It is not for general publication.

If you’ve not already done so, download the free templates from this article.

Conclusion

The process of stakeholder engagement helps build trust among your stakeholders. It allows you to identify the power centers – the people and organizations that have influence over your work. It can help you gain support for your initiatives and acceptance of your plans.

The foundation of effective stakeholder engagement is a robust and ongoing process of stakeholder analysis. By segmenting stakeholders by power and interest, you will be better able to focus your time and attention.

To your success,

Mike

What’s on your mind today?

Do you have a management problem or question that I could help answer?

If so, then let’s talk.

Click on the button below to schedule a complementary 30 minute conversation. We’ll work together to identify some actionable ideas.

Footnotes

1 As often happens, when I went searching for the historical origins of the words “stake” and “stakeholder”, I found various definitions and conflicting historical accounts. The British author and management consultant Mike Clayton, in his book “The Influence Agenda”, cites the Oxford English Dictionary:

According to The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edn, 1991), the word ‘stakeholder’ first appeared in 1708, meaning the holder of a wager. A stake is ‘that which is placed at hazard’, although the OED is uncertain where that usage of stake comes from.

Several sources mentioned work done at Stanford Research Institute (SRI) in the 1960’s that resulted in our modern definition of stakeholders. I found two mentions that credit Marion Doscher, a technical writer at SRI, with first using the term “stakeholder” in a business context. According to one source:

Doscher defined them as ‘stakeholders’, to her an old Scottish term meaning those with a legitimate claim on something of value.

That author then continued with a third interpretation:

Actually, its semantics go something like this: stakeholder is literally the holder of a wager but stake is also short for grubstake, an early U.S. Western term meaning an advance given to a prospector in expectation of a share in his finds.”

That’s the answer I was looking for! I grew up watching TV westerns, which often featured tales about the California gold rush of 1849. A miner’s “stake” was the parcel of land – or river – he claimed and where he expected to find his fortune. These were closely guarded and often fought over.

Image from a collection of photographs organized on Pinterest by Frances Newsom-Lang.

2 Mike Clayton has published a number of books and videos on various aspects of project management. In this five minute YouTube video he describes his approach to Stakeholder Engagement.