Introduction

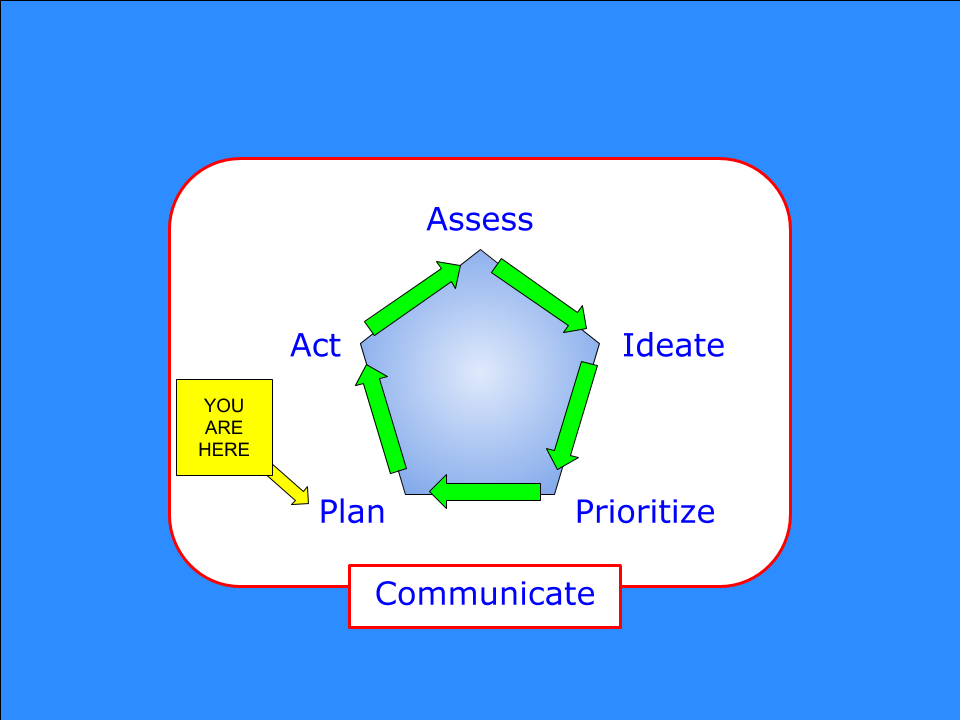

The fourth phase in the planning framework is Plan. This is where the magic happens. All of the effort we have put into the earlier phases now comes together as we begin developing the plan.

This is the latest in a series of articles about planning in uncertain times. In the first article, I introduced the framework – a repeatable cycle made up of six phases. The other articles are:

- Phase 1 – Assess

- Phase 2 – Ideate

- Phase 3 – Prioritize

- Phase 4 – Plan

- Part 1 – Developing a Plan – this article

- Part 2 – Refining Your Plan

- Phase 5 – Act

- Phase 6 – Communicate

This article is the first of two that will focus on the fourth phase of the cycle – Plan.

The final article of this series will explore the Act phase.

In the Plan phase we will determine how to implement the actions identified in the Prioritize activity and identify the measures of success. For each of the prioritized actions, we will ask and answer questions like:

- How should we do it?

- In what order?

- Who will do it?

- What obstacles or interdependencies could impede progress?

- What will it cost?

- What are the risks?

- How will we measure progress and success?

We will organize our answers into a project plan that can be executed in the Act Phase that follows. In an earlier article, “The Building Blocks of Success – Part 2”, I said that developing a plan is an activity that should feel familiar to many readers. It will utilize processes you probably already have in place – most organizations have methods for planning and executing projects.

I don’t intend this to be a tutorial on project planning. There are many credible sources readily available. (See the Manager Resources page for some suggestions.) In this article I will provide some actionable ideas that will complement most project planning methods.

Two Definitions

There are two definitions that will ground our discussion of Plan phase activities.

The first is a definition of “planning”. My working definition is:

Making decisions about how and when to allocate people and resources to achieve organizational objectives.

A key word there is “decisions”. When you are developing a plan you make a series of trade off decisions. In each phase of the planning cycle, we have asked and answered questions as we developed the details. You have already made some important decisions in earlier phases of the planning cycle, including:

- Selecting an assessment topic

- Identifying the most relevant opportunities

- Determining which proposed actions to pursue

There are more decisions to make while developing the plan.

The second definition is “project”. The Project Management Institute defines a project as “a temporary endeavor undertaken to create a unique project, service or result.”

As you develop your project plan, you will make a new set of decisions that may involve other work underway in your organization. In order to pursue the proposed actions, you may have to temporarily stop other work in order to reallocate people and resources to the new plan.

These two definitions fit together neatly. You create a plan to achieve your organizational objectives. In this planning cycle, we are talking about objectives that should produce long-term or permanent change in your organization. In order to execute the plan, you will make a series of short-term decisions about what work gets done and what gets delayed.

Peter Drucker recognized the importance of balancing today’s needs with those of the future.

“Management always has to consider both the present and the future; both the short run and the long run. A management problem is not solved if immediate profits are purchased by endangering the long-range health, perhaps even the survival, of the company. A management decision is irresponsible if it risks disaster this year for the sake of a grandiose future.”1

Once the project is successfully completed, you will make other decisions about any work that was postponed. The changes implemented in your organization may make the old work irrelevant. That is a discussion for another day.

Objectives and Outputs of the Plan Phase

There are two objectives of the Plan phase:

- To develop a comprehensive, actionable plan that addresses the prioritized actions.

- To define measures of progress and success.

The outputs of the Plan phase are:

- A detailed plan that shows tasks, assignments, durations and resource estimates.

- A list of assumptions made during the creation of the plan.

- Updated notes on conflicts and interdependencies.

- Cost estimates for planned activities.

- A “risk register” that captures information about risks and mitigations.

- A set of measures to track progress and evaluate success.

The Plan Process

There are five steps in the Plan phase:

- Assemble the team

- Develop the draft plan

- Refine the plan

- Develop the measures

- Communicate

In this article, we will cover the first two steps. The next article will cover the last three steps.

Assemble the Team

In “The Building Blocks of Success – Part 2” I suggested that planning should be a team sport. You will need input from other people and teams in order to construct a plan that is comprehensive and actionable. You and a small team can do the first draft, but you will need to consult with others before finalizing the plan. Any person or team responsible for a task in the plan should have an opportunity to review, comment and modify the task to reflect their capabilities and capacity. Without commitment from all participants, your plan will be at risk.

Build the Draft Plan

There are nine tasks to perform when developing a draft plan. (Now you can understand why I split the Plan phase into two articles!)

1. Collect Your Inputs

During the earlier phases of the planning cycle, you created several documents that will be important inputs to the Plan phase activities. They are:

- From the Assess Phase:

- The original assessment topic – the major issue or opportunity that your planning efforts are intended to address.

- Outputs from the SWOT and PEST analysis.

- From the Ideate Phase:

- Idea Maps for each relevant opportunity

- One Page Summaries of proposed actions

- How-To-Do-It lists – ideas on how to implement the actions

- From the Prioritize Phase:

- A prioritized list of proposed actions

- Updated One Page Summaries

- Notes on interdependencies and conflicts

If you have new people involved in this phase, it may be necessary to do a brief review of the earlier phases and the outputs to ensure that everyone shares a common understanding.

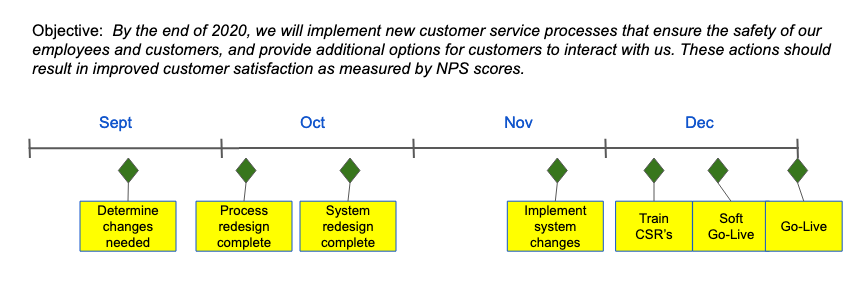

2. Define the End State Objectives

In the definition of planning, above, we said that a plan exists to “achieve organizational objectives”. During the Assess Phase, you identified an assessment topic as a focus for your planning activities. The assessment topic reflects a problem, issue or opportunity that your business or organization is experiencing now or anticipates in the future. Your objectives should state the outcome of addressing the assessment topic.

For example, if your assessment topic is “How should we refocus our customer service organization to operate in post-COVID environment?”, your objective statement might be:

By the end of 2020, we will implement new customer service processes that ensure the safety of our employees and customers, and provide additional options for customers to interact with us. These actions should result in improved customer satisfaction as measured by NPS scores.

Another approach is to ask questions like:

- What will success look like?

- What will be different when we successfully implement our plan?

Whatever approach you take to defining the objective, make certain that you state it as a SMART objective, one that is Specific, Measurable, Assignable, Realistic and Time-Related.

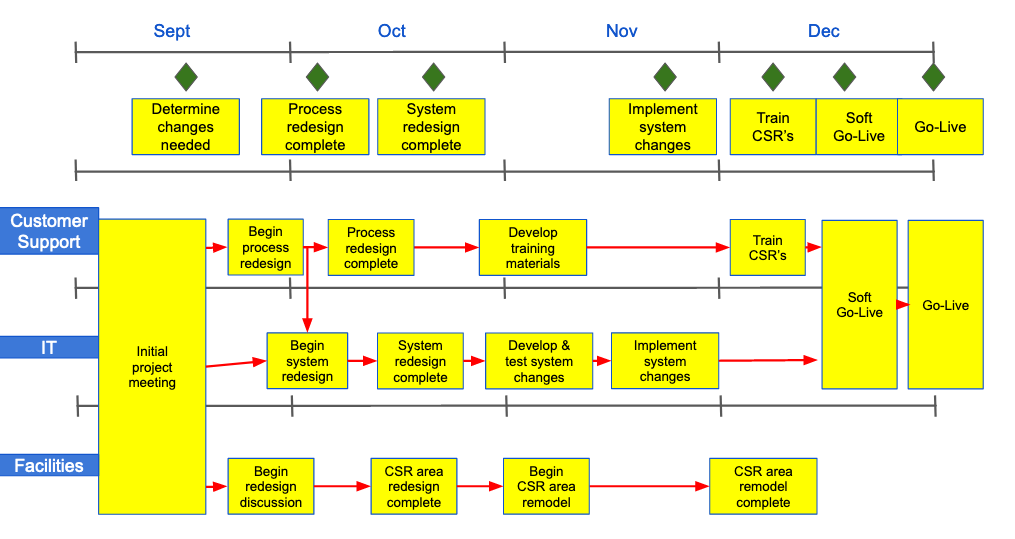

3. Sketch the High-level Timeline

A good way to start developing a plan is to draw a simple timeline that begins now and ends when the proposed actions are successfully implemented. Use an appropriate high-level timescale for the timeline. If your plan will take a year or longer to accomplish, divide your timeline by quarters. For shorter duration plans, consider dividing it by months.

Using your input materials and the collective wisdom of the team, identify the major milestones that will need to be accomplished in order to achieve the objectives.

Don’t get too granular yet. Keep the team focused on the top level milestones. This may be a challenge, as some team members will want to jump into the lowest level details. Capture notes for later, but keep them focused on the forest, not the leaves on the trees.

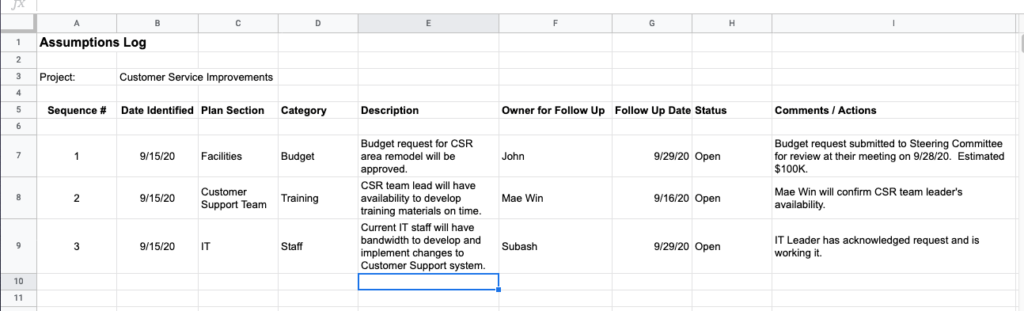

4. Capture Your Assumptions

Every plan is, in many ways, an educated guess about how you will achieve your results. To create a plan, you have to make some assumptions – about costs, staffing requirements, market trends, the weather, or any of dozens of other variables that could influence your activities and over which you have varying degrees of control. It is critically important that you identify and document these assumptions, because they influence how you create your plan. And, if an assumption proves to be incorrect, it can impact your ability to successfully deliver your results.

As you are developing your plan, these may seem like eternal truths or common knowledge. But later – during a review next week or in six months – a question is sure to arise about why you thought you should do it this way. I can almost guarantee that you won’t remember the answer.

But if you document your assumptions, you can answer the question and then focus any subsequent discussion on the validity of the assumption. If the assumption needs to change to reflect new information, your plan can be updated.

Identifying assumptions can be challenging, since many assumptions about our businesses are unspoken or so deeply ingrained in our culture that we don’t think about them. But there are verbal clues that indicate when assumptions are being made. Some examples are:

- “If – then” statements. “If we did this, then we could do that…” The “If” clause is the assumption. For example: “If we launch the new product line, then we can afford to hire the additional staff we we need.”

- Statements about constraints. “We will only have $10,000 to spend” or “We won’t be able to hire new people”. In these cases, the assumptions limit the possible actions you can take in your plan.

- Statements about resources. Some assumptions are about the availability of resources needed for the project. “The learning lab will be available and adequate for our needs” or “Our existing warehouse will have enough space to store new products prior to launch.”

For every assumption you identify, you should capture several bits of information, including:

- The date the assumption was identified.

- Which section of the plan it applies to.

- A category, like “Resources”, “Budget”, etc.

- A description of the assumption. (Be as specific as possible.)

- The person or group that owns the assumption and will be responsible for following up to verify its accuracy or validity.

- A date when the owner will validate the assumption. (Add this as a task in your plan.)

- Status of the assumption: Open or closed.

- Comments about status, new findings or other actions needed.

An example of an assumptions log is shown below.

I have created a simple template that you can use to capture your assumptions and the related details.

Download the assumptions log template.

Identifying assumptions is a skill that is learned over time. Early on, It may be helpful to identify someone who can listen for these, ensure that they are clarified and record them.

5. Add Swim Lanes

Once you have the top level milestones, you can begin to get into the details. An important aspect of developing a comprehensive plan is to ensure that all major parties – the teams or organizations that will contribute to the success of the plan – are represented in the planning process. Adding “swim lanes” to your timeline is one way to make certain that all participating groups are represented.

Look across your timeline and ask “Who needs to participate to make this plan successful?” Add a swim lane for every team you identify.

Then, to the extent you are able, add major milestones to each of the swim lanes. These will still be high level items. Many will simply represent interdependencies between your team’s work and the work of other groups. If another team is not present, you will need to arrange time with them to review the plan and solicit their input.

As you did in the earlier step above, capture notes about any assumptions you make about the participating groups, the interdependencies and the milestones.

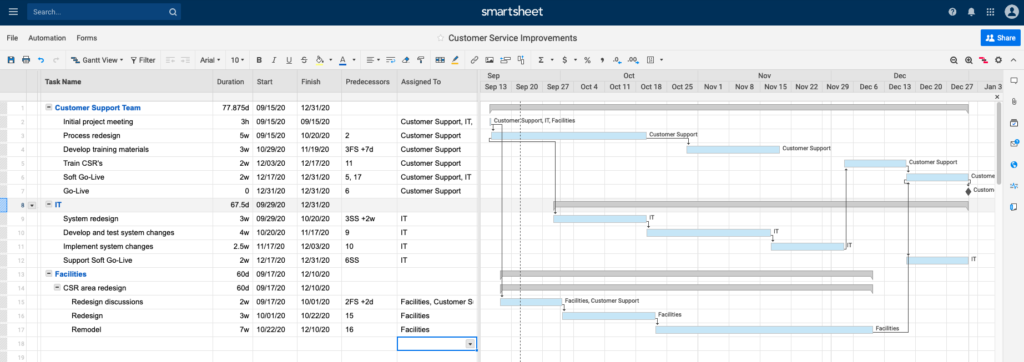

6. Add the Detailed Tasks

Now you’re ready to get “down in the weeds” – identifying the detailed tasks that must be performed to deliver the high level milestones in each swim lane. At this point, it will make sense to shift from the visual depiction of the timelines to a more structured planning tool that can record the details. Excel and Microsoft Project are commonly used tools. Many new tools are available online, like TeamGantt, SmartSheet, Wrike, Trello, Monday and Asana.

One way to organize the plan details is by swimlane. Each swimlane label can be a section header in a project planning tool.

A caution about tools: Don’t get lost in a lengthy tool selection process. Use whatever tool your organization has adopted or that you feel most comfortable with. Encourage your team to devote their energy to capturing the details needed for the plan, not debating the pros and cons of different tools.

Here are some details you should define for each task:

- A description of the task. Include as much detail as is necessary to ensure the team understands the work to be done.

- Who will perform the task. This could be individuals or teams. Just make certain that every task has an assigned owner.

- The estimated duration of the task. How many hours, days or weeks will be required?

- Estimated start and finish dates. If you’re using a tool like MIcrosoft Project or TeamGantt, the software will do most of the calculation for you.

- Dependencies and prerequisites. Many tasks will be dependent on some other task being completed. The corollary is that many tasks will be prerequisites for others. Again, most software tools for project management will link tasks together to capture the interdependencies.

- Finally, capture notes on any assumptions or unanswered questions about the task.

7. Identify Other Resources Needed

As you work out the details, you may discover needs for additional resources like tools, training, special facilities, executive support or funding. Insert tasks in the plan that cover the acquisition of each new resource.

You should also update your list of assumptions if there is any doubt about whether the necessary resources will be available. An Example: “Assumption – Our request for $100K in additional funding will be approved by the Steering Committee.”

8. Note Conflicts and Interdependencies

As the teams add details to their swimlanes, it is likely that they will identify conflicts that are not immediately resolvable. This often happens when participating teams are from different organizations where priorities may be different. Highlight these in your notes and assumptions. If needed, add specific tasks for conflict resolution.

9. Iterate

I’ve never seen a plan emerge fully detailed from a single conversation, so it’s important to allow time for several iterations. It’s likely you will need time for other teams to complete their detailed plans and submit them. If there are unresolved conflicts, these may need to be worked out prior to moving ahead.

Another caution: Don’t get caught in endless iteration cycles, what is commonly referred to as “analysis paralysis”. Your plan will only be complete on the day you finish the work. Up until then, it will change as new information arrives. Remember the words of General George S. Patton,

“A good plan, violently executed now, is better than a perfect plan next week.”

General George S. Patton

I’m sure we all hope our plans will not require violent implementation, but the General’s point is well made. When you are developing your plan, there is a point of diminishing return where additional iterations beyond a certain point add very little value.

Conclusion

In this article we covered the first two steps in the Plan phase – assembling the team and developing the draft plan. The next article, Refining Your Plan, covers the remaining three steps – refining the plan, developing the measures and communicating status.

Thanks for reading this far. If you have questions or strong reactions, please leave a comment below.

To your success,

Footnotes

1 Peter Drucker, Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices (New York, Harper Colophon, 1985), p. 43

What’s bugging you today?

Could you use some help with a management problem or question?

If so, then let’s talk.

Click the button below to schedule a complementary 30 minute chat. We’ll work together to identify some actionable ideas just for you.